People exchange Instagram QR codes in New York on Aug. 8, 2021. Among teens, Snapchat and TikTok overshadow the service. Credit – Molly Clark – The New York Times/Redux

Lena Kalandjian remembers struggling to recreate the makeup she saw on beauty tutorials on YouTube and Instagram when she was 13. No matter how much money she spent on expensive products or how much time she spent practicing her techniques, her makeup face never seemed to match the creators she was emulating. This made her feel stressed and frustrated.

She says: “I would spend all my Christmas and birthday money on these products that are supposed to make you look flawless.” “And they’ll never look as good on me as they do online.”

Kalandjian, 18, is a senior at North Broward Preparatory School in Coconut Creek, Fla. She said it took her years to realize that the finished product she sees on social media is usually the result of a combination of lighting, editing and filters. “In real life, you’re always going to have textures and flaws in your skin,” she says. “No matter how good a makeup artist you are, there’s nothing you can do about that.”

One day, Karanjian says, she began to understand the enormous impact social media has on young people’s mental health and the formation of their self-identity. This realization came from an unlikely source, during an English class where students watched the Netflix documentary “the Social Dilemma,” which revealed the ways in which social media platforms manipulate and influence their users. More importantly, she realized that any problems she encountered on social media were not her problem alone. Instead, they were part of the platform’s design.

“When I was a teenager, I felt that if you’re addicted to social media, it’s your responsibility to be aware of it and to quit social media when you’re spending a lot of time online. It made me feel guilty about playing on my phone all the time,” she added, worrying that social media used to keep her awake at night. “But after seeing how these platforms are designed to maximize your usage, I thought, well, they never told us that they were keeping us from getting off the bus.”

Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, has denied claims that it is putting profits ahead of user safety. A spokesperson said in a statement:Â “As a company, we have every business and ethical incentive to give as many people as possible a positive experience on our apps.”

Since learning why online content could wreak havoc on her self-esteem, Karanjian has made it her mission to help other young people avoid the same fate.

Her school is just eight miles from the site where 17 students were killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High in 2018, a tragedy that brought the issue of student safety to the forefront of community concerns. Kalangian was connected to Students Against Violence Everywhere (SAVE), an affiliate of the Sandy Hook Promise, a nonprofit organization that prevents gun violence and is an umbrella for a national network of student-led organizations dedicated to keeping young people safe.

Across the country, thousands of SAVE Promise Club members are working for the safety of young people, a mission that is increasingly intertwined with protecting them from the dark side of social media. The issue is only becoming more urgent. Last fall, whistleblower Frances Haugen claimed that Meta underestimated her own research about the harmful effects of its platform on teens, which included eating disorders, depression, suicidal thoughts and more. Her testimony sparked months of news coverage and congressional hearings about the impact of social media on the mental health and safety of young people. Then, in early May, a 16-year-old girl filed a lawsuit against Snapchat, accusing the company of failing to protect young users from sexual exploitation.

Time magazine interviewed three students, including Karanjian, who heads the 13-member national youth advisory board of the Save the Promise Club, and asked their views on how teens can help keep their peers safe online.

This anecdotal evidence is supported by professionals in the field. says Sosana Fagan, a clinical psychologist at the Franciscan Children’s Clinic in Brighton, Mass. She says young patients she has worked with have found a similar correlation between time spent on social media and increased emotional distress. She says: “They found that by taking social media vacations or limiting the amount of time they spent on certain platforms, they were able to better realize their self-worth.”

Aashi Mittal, a 17-year-old senior at Del Norte High School in San Diego, said her parents were wary of her using social media at too young an age. So she waited until her freshman year of high school to sign up for her account – and soon found that the pressure to be “perfect” online could be overwhelming. She says, “We see this picture of life on social media all the time, where everyone is happy, hanging out with their friends, doing fun things.” “It can lead to a very negative self-perception.”

When she started using Snapchat and Instagram, she had to learn how to deal with that feeling, which sometimes overwhelmed her when she saw posts from friends or influencers that made their lives seem perfect. That’s when she really understood her parents’ hesitation. She says: “A big part of self-care is creating a healthy online environment for yourself and staying off social media when you need to.”

In recent years, Instagram has become a hotbed for young women to take unrealistic and often unattainable photos of their body standards. in 2019, the New Yorker published an article titled “The Age of Instagram Face,” which explored how Facetune and other The New Yorker published an article titled “The Age of Instagram Face,” which explored how editing apps like Facetune, as well as increasingly frequent plastic surgery, have spawned “single cyberfaces” among the “professional beauties” on the photo-sharing platform.

To counter the harmful effects of online social climbing, Mittal founded the school’s SAVE Promise Club, which organizes a number of mental health awareness programs focused on self-care through social media. Ironically, some of these programs run on the same platforms, which exacerbates the problems. “It’s kind of like the 22nd Military Rule,” she says. “A lot of the information has to do with taking care of yourself offline. But then I’ll share it online.”

Why not log off?

It’s not as simple as saying teens should disconnect altogether. Not only has social media been compared to tobacco for its level of addiction, but it’s also become an integral part of young people’s lives – especially since the pandemic began. In a 2018 report that says,Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in the United States online shows that teens spend an average of nine hours a day, Common Sense Media reports that in the last two years alone, non-school-related time spent on screens among 8 – 18 year olds has increased by 17 percent.

“It’s a vicious cycle where if you don’t have social media, you feel like you should be using it. But once you’re on it, you feel like maybe you should get off it,” Mittal said. “It’s really hard to stop because the more people who use it, the harder it is to still feel a sense of belonging without it.”

At Kalangian’s school, Michelle Henne, a history teacher and cheerleading coach, adviser for the SAVE Promise Club, said social media clearly dominates students’ lives. “They’re online from the first thing in the morning until they’re supposed to be in bed,” she says. “If they don’t have their phones, they feel like they’ve lost all connection to the world.”

But part of the problem is also that social media isn’t all bad. Communicating with friends online gives young people an essential support system when “peer interaction is critical to their social, emotional and even moral development,” says Fagan.

Although the system works against them, the positive aspects of social media give Karanjian hope that it can still be a “force for good” for young people. “Social media is going to come into our lives whether we like it or not,” she says. “So it’s important to know how to use it responsibly, rather than hearing people say, ‘Your life could be so much easier if you didn’t use it at all.’ That’s not the solution.”

Because previous generations didn’t grow up with the same access to social media, some members of older groups sometimes don’t appreciate the inherent role social media plays in young people’s perceptions of themselves and others. “You can see elementary school students already watching YouTube on their iPads,” says Chris Nguyen, an advisor to the SAVE Promise Club and a science teacher at Soomro School. “They start using social media at a very young age, and as they get older, they become more and more dependent on social media.”

Mittal said parents and other adults need to be aware of why things online can sometimes feel one-and-done in a teen’s life: “Adults don’t always understand why issues that seem small and insignificant, like getting certain comments or not getting enough likes after, make us feel bad.”

What’s next

In an effort to rein in the power of big tech, lawmakers are passing the Kid’s Internet Safety Act (KSA), a bipartisan bill that would create a social media platform responsible for preventing harm to minors by providing them and their parents with the option to protect their personal data, disable addictive product features, and opt out of algorithmic recommendations.

But there is no guarantee that the Senate will vote to pass the Corsa bill – there are concerns about whether the legislation would violate teenagers’ privacy – and young people like Karanjian, Mittal and Somro realize that no matter what happens in Congress, their work Frances Haugen herself is championing a broader youth-led social movement to pressure social media companies from young people to reform their ways. She recently told the National Education Association (NEA) that students should be leaders in demanding more accountability from the tech giants.

For the teens interviewed by Time magazine, graduation is just around the corner.

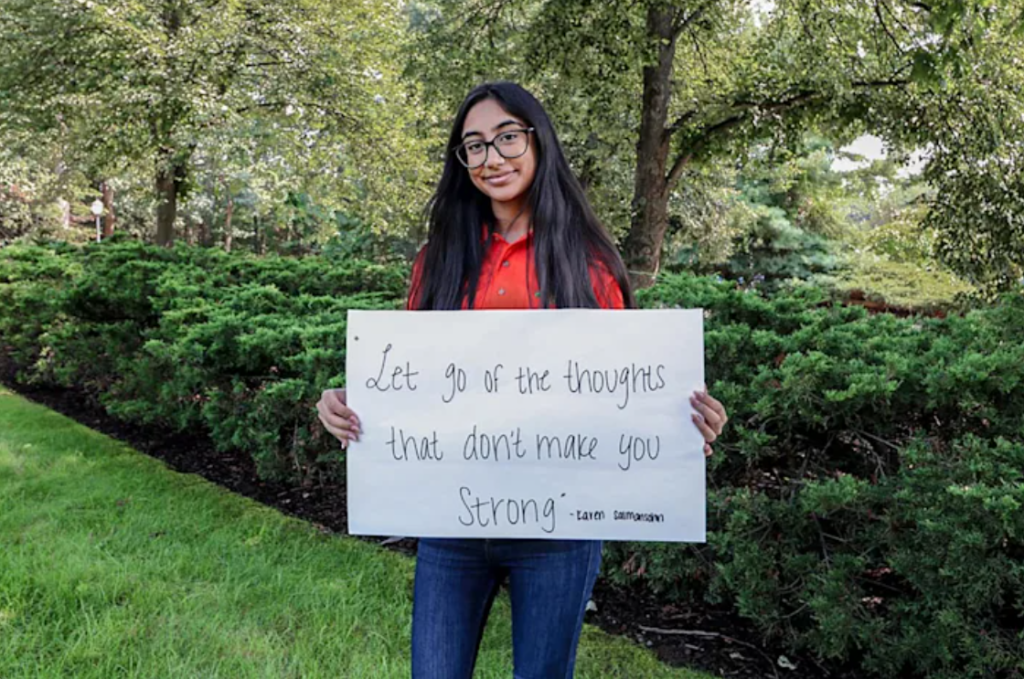

Soomro is currently training juniors in the school’s SAVE Promise Club, teaching them how to run social media workshops after graduation. She says: “Doing this research and educating others has made me more aware of the time and energy I put into social media and inspired me to help others set their own boundaries.” “Hopefully, this will be my legacy and the school will continue to do so.” This fall, she will be attending the University of Texas at Austin to study political communication.

While Mittal hopes to continue to engage young people in a healthier relationship with social media, she knows what she has already accomplished is especially impactful. She says: “I’m at that age myself, and it’s really empowering to be able to talk about these things.” “All the work I’m doing now is special because I’ve been through it.” After moving across the country, she will begin her pre-med studies at Williams College in Massachusetts this fall.

For Karanjian, she hopes to incorporate this radicalism into her education and career from now on. In addition to a recent TEDx talk on online social comparisons, she presented a social media webinar in partnership with the National Center for School Safety at the University of Michigan.

There, she spoke to an audience of educators and mental health professionals about their blind spots when it comes to teens and social media. She said:We need to agree on how to do better together.”

Next year, Kalandjian will attend Vanderbilt University to study human tissue development. She says she wants to put her experience to work building better institutions, no matter where her path takes her. She says, “It’s definitely going to be something I’ll remember for the rest of my life.”